The Science of Creativity – Lauren Trangmar

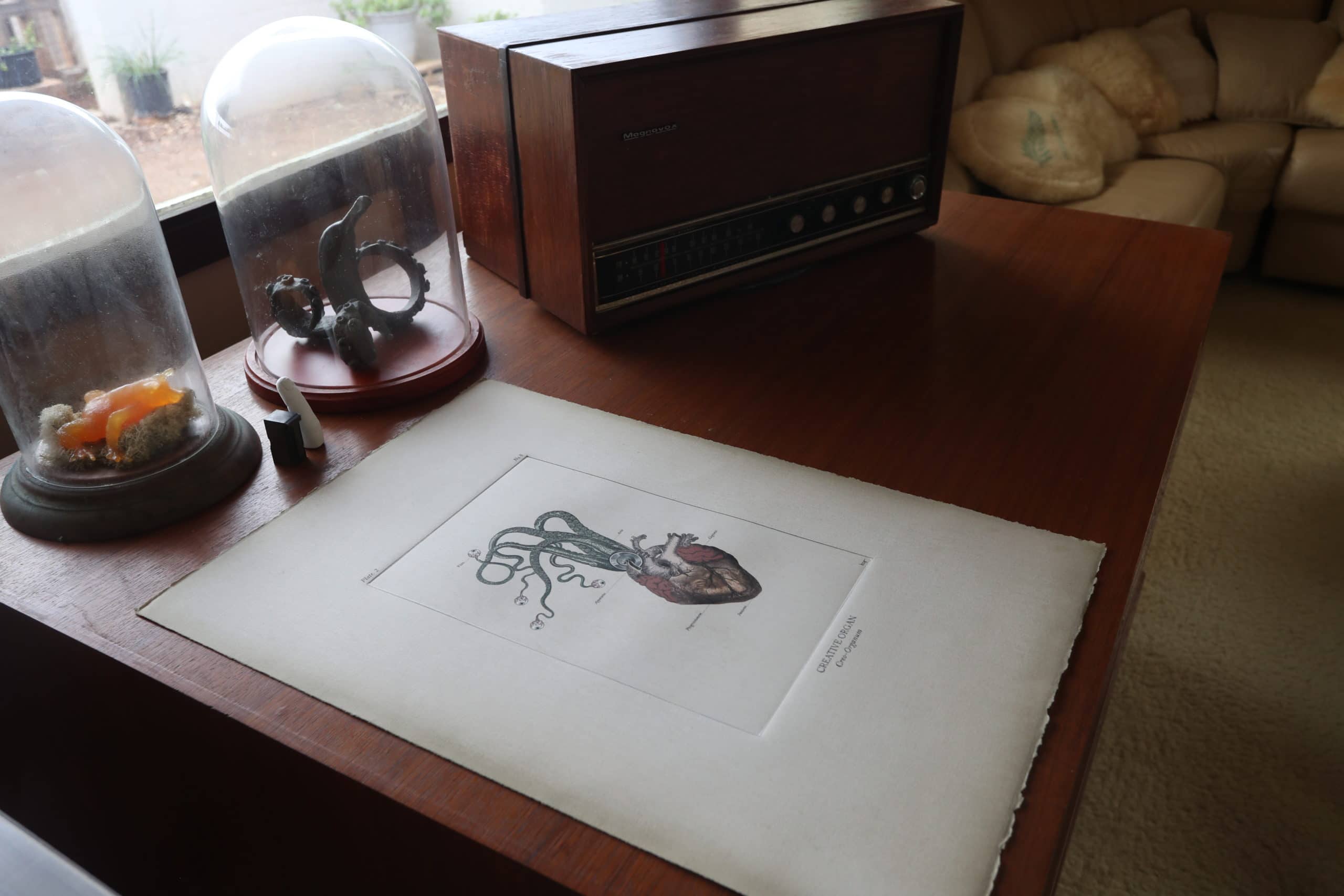

A deconstructed saimin sloshing wildly within its bowl. A map of the United States from the perspective of Hawai‘i. An astrological chart with a hodgepodge of curious creatures darting to and fro. Welcome to the world of illustrator and artist Lauren Trangmar. With a visual language that draws on history, science, and an uncanny combination of strange things, Lauren is on an artistic quest to illustrate the creativity that can be found within all objects. She combines illustration, digital imaging, traditional printmaking, painting and sculpting to create incredibly detailed and alluring works of art. An Orvis Artist in Residence at the Spalding House, Lauren’s work can be found at the Honolulu Museum of Art and Nā Mea Hawai‘i. We sat down with Lauren to talk about old medical books, visual representations of creativity, and what it all means.

Your illustrations are so alive. They have this very distinctive style that draws from historic scientific illustrations. How did you get interested in scientific drawings?

I started doing that work when I was at U.H. Mānoa. I remember being stuck on a project and going to the library to look at books. I got stuck in the science section, drawn in by Gray’s Anatomy—not the TV show but this series of human anatomy books with anatomical drawings for doctors. There are 41 versions starting in 1858. I was attracted to the level of detail and the style of the drawings. Science didn’t have photography yet, and because Gray’s Anatomy was a medical book, it was taken as fact. But it isn’t accurate now that we’ve gone further and can see what’s really there. It’s interesting to play with that, the evolution of fact. That’s something that drew me in and got my ideas rolling in storytelling through fact and history.

What is it about the scientific diagram that allows you to raise questions and make statements in a provocative, yet easy-to-digest way?

Science is the language of drawing. Stylistically, I can show factual and relatable things in the natural world, but then I can break it down. I am endlessly curious about how things work, so I’m researching and referencing science and history, but being able to do it in an artistic way is perfect. I like breaking down complicated ideas and re-presenting them in a way that is visually stimulating and easier to understand, but also makes the viewer curious about what is represented. I think a lot of people naturally have a desire to understand their surroundings—natural and cultural—so I’m breaking things down and presenting them through an artistic, yet scientific and educational lens.

Your maps are a great example of your penchant for scientific and historical storytelling.

I just did a map recently and I was looking at the history of maps in Hawai‘i. They could only show what they knew at that time, so these drawings change over time based on the information and technology they have. I made up a map of my own creative journey, the people and things I’ve been exposed to in my life, and I did it the way old maps used to do it with all the symbols, all the detail. There is science in there, but then there is storytelling that allows me to tell a different story that doesn’t come from somewhere factual. It’s hard to explain, but it comes naturally to me, it’s a like a reality with a bit of a twist.

When you create these drawings, you’re using a range of old and new techniques. Can you share with us your artistic process and how your illustrations come to life?

I’m always exploring relationships between storytelling, art history, technology, culture, myths, history, art, and science. Both of these are binary. There are always bits of that in my work. I start with the topic and I do a lot of research delving right into every detail I can find. I extract the parts I find relevant to the info I need to convey. I like the obscure bits. I throw little weird things in there that make things interesting. My process varies from project to project, but generally it starts with an idea, then I do the research, and then I sketch and play around with composition. Once I get a solid design I do the black outlines and eventually get to the color. The outlines are done in ink pen, on a digital drawing tablet, or drawn and inked up on a printmaking plate, and the color is painted with watercolor or done digitally. Most often, I end up mixing and matching processes a lot to get the best results.

Juxtaposition seems to be a recurring tool you use to tell stories within the illustrations. How does this help get your point across to the viewer?

I like the way storytelling and illustration can make the strange familiar and the complex understandable. Juxtaposing things that don’t seem to go together is a way for me to tell stories about things that don’t naturally go together, but are actually part of a larger system or story that does make sense, even if that’s just within itself. It’s that little twist that I like, and that’s the beauty of being able to illustrate things.

Why does taking an ordinary item, say a plate lunch, and deconstructing it in a scientific drawing make that item so much more interesting?

What I like about illustration’s role in this is that it can bring a different kind of understanding to things. As an illustrator, I can work in a place in between the natural world and the imagination, but where they both strongly depend on each other. I can add a bit of whimsy, a little extra character, give something more than what you might see in a photograph or in a real life encounter to enrich the story or understanding of my subject. And people gravitate to this. The everyday stuff that we take for granted, like the plate lunch, there’s a long history behind all of these things. I love all the stories of where things come from. I get inspiration from these stories. It’s just another way of looking at these things, the way it’s made—there’s a science and history to it.

Your work is heavy with metaphors, what’s the best way for people to engage and understand your artwork?

I have been including informational cards with my work and write out as much as I can now. In the beginning I didn’t think anyone would care, but with my cosmology map, I had an entire sketchbook of notes. I was using them to create the work at that point. Then the curator I was working with wanted me to do something with my notes. So I organized my sketch notes, designed a book, put in all the meanings, research and writing, and put it in the show. I didn’t think anyone would take the time to read it, but it ended up being sought after. People loved it. From then on I include my writing.

What’s next on your creative horizon? Any new installations?

I have a few projects I’m working on. I’m doing a few more maps and I’d like to look into botanicals and wildlife specific to Hawai‘i. And I’d like to do more illustrative wallpaper. I’m really fascinated with Toile fabric. It’s a style of really detailed old wallpaper and fabric that have all these fanciful stories in them. I’ve got lots of birds in the universe that I’m waiting to come back to me. I’m also currently working on a large drawing on a column at the entrance of the Impact Hub across from Whole Foods Queen. It’s a large illustrated mural, but I’m drawing it all. I researched the history of the Ward area. I pooled the information and mapped it out on the column to draw it all. I just did the outlines. It’s relative to how it would be laid out on a map. There are all these little pockets of things going on relative to each other. It goes from Kewalo all the way up to the Blaisdell.